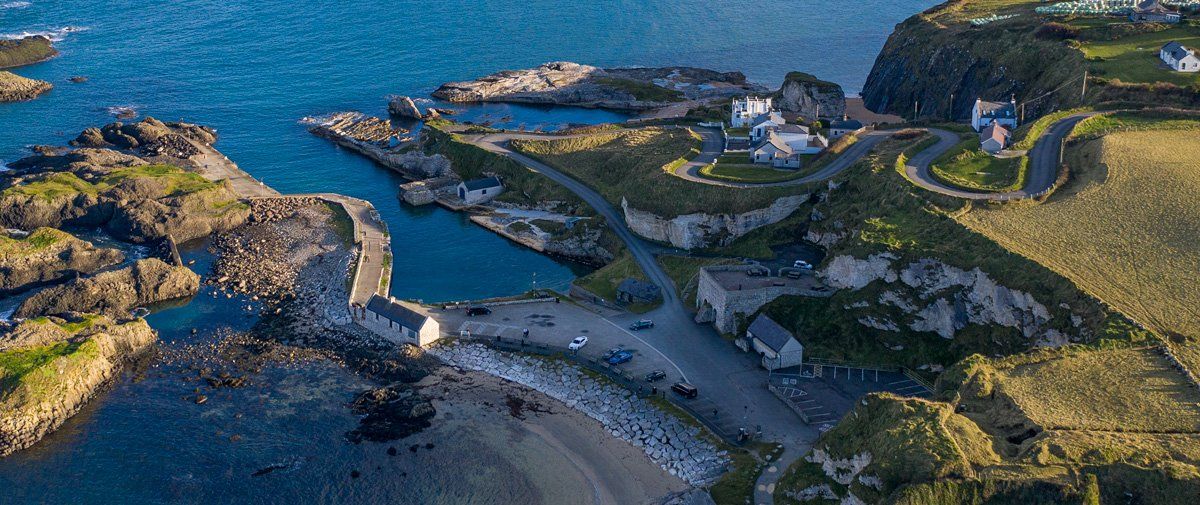

The winding road down into picturesque Ballintoy harbour was originally the access to an industrial limestone quarry and fishing harbour which would have been a hive of activity. The harbour, built from limestone blocks and surrounded by limestone cliffs was once a hub for north coast fishing, boat building and the local industries. The harbour is well sheltered from the Atlantic by scores of black basalt islands and looks out across Boheeshane Bay to Larry Bane Head, Sheep Island, Rathlin Island and Scotland. Herdman, McKenna & Company began limestone extraction here at the beginning of 1860, they also built the harbour, the twin kilns, and rail tracks for moving loads to the quay.

In June 1860 Antrim Borough commissioned the construction of a new road from Ballintoy Church down to the harbour for improved commercial access. By 1861 the lime works know as 'Ballintoy Lime Work's was up and running, exporting product to Ayrshire and Glasgow for use in iron smelters with the twin kilns being fired by Ballycastle coal and local lignite. In 1878, William Herdman tragically fell to his death from the quarry face and the following year Eglinton Chemical Company leased the Ballintoy Lime Works from the Herdman Estate. The company already had the limestone assets of Larry Bane leased and were manufacturing and exporting sett stones from the harbour.

The kilns have now been given grade B1 listing which provides a level of protection and maintenance. The superbly built lime kilns both here and at Larry Bane stand as a testament of our rich industrial heritage. Burnt lime would have been drawn away from both sites by horse and cart contributing to the building of hundreds of local stone cottage and rural halls. Ballintoy is still a working harbour for local fishermen who continue a tradition that goes back to when man first arrived here. It naturally produces good boatmen due to the dangerous waters which they and their fathers have come to understand, respect and work upon. The large boat cave to the right of the car park would have been used to repair, layover and build boats.

Though scores of basalt islands act to shelter the harbour from prevailing storms, it can still on occasions get battered, in my lifetime I have seen waves riding over the armour walling (installed to prevent it) and washing car park in front of O'Rourke's Kitchen. The last big rock as you leave the harbour on the left-hand side is known as Rock-an-Stewart and was the scene of a tragedy and brave rescue in April, 1884. The Giant's Causeway guides were returning from their annual trip to gather spar from the cliffs near Kenbane Castle, this would later be displayed in small boxes and sold to visitors on the pathway down to the Causeway Stones during the summer months.

Onboard were John, Hugh and James McLaughlin accompanied by Robert Hutchinson. A young boy named John McFaul who lived at the Causeway and was employed by John Robinson at Carnduff, near Ballycastle, took advantage of a boat ride home. There was a swell running which was producing a sizable roll on the sea, closer inshore it was creating breakers. As they approached Rock-an-Stewart a large swell wave broke and they were caught on the inside. The wave capsized the boat and flung everyone into the water. John McDonald who was manning the Coastguard Station on the cliff above had been watching the progress of the boat across the bay and witnessed the accident.

He immediately rushed down to the harbour and was joined by John Jarrett and James McNeally (Coastguards) along with Bryan O'Roarke and Richard McKay (Fishermen), they quickly launched a boat and headed out into the breakers. Due to their skill and great courage they were able to rescue John and Hugh McLaughlin along with Robert Hutchinson, all three were still holding on to the upturned boat which was amongst broken water and close to the rocks but there was no sign of James McLaughlin or young John McFaul whose lives the ocean claimed.