Aqua vitae (water of life) is a term for distilled spirit (whiskey), it was first recorded in England during the reign of Henry II (1133-89), the opinion suggests that Ireland was aware of distillation before England, due to the affinity between the Irish language and those spoken in Asia and also the connection Ireland had with the wider world at the time. The art of distillation either came here directly from India, or via Spain or Italy where it was known as Aqua vite or Acqua di vite (water of the vine). The grape is the source from which spirit was extracted in those countries. Christianity brought religious settlements through Europe and into Ireland, the latter become known as the land of 'saints and scholars', and was an important centre for Christianity and its spread back into England and Europe.

Whiskey Heritage

Whiskey Heritage

These monasteries where not only places of worship and prayer, they were centres of learning, science and many also acted as medicinal dispensaries or places of healing. It is believed the term acqua vite(water of the vine) was corrupted into the latin aqua vitea (water of life), to give a clear distinction between a spirit distilled from wheaten malt and a spirit produced from grapes. We can surmise that the early process of distillation other than from the grape in Ireland, was made in monasteries, many people of power and wealth were patrons of monastic settlements and would have had easy access to the process. The spirit produced was called 'aqua vitea' and it was used for medicinal cures, a panacea for many ailments and purposes.

There are accounts of physicians recommending it for the reduction of tumours, strengthening the heart, colic, dropsy, palsy, fever and many more. Aqua vitea was also believed to have properties that could prolong your life beyond expectation. This made it sought after and the attachment to it grew over generations, in many ways you can understand why its use and production went out of control during certain periods of history. It is also apparent that 'aqua vitea' was used in Ireland in a similar way opium was in parts of the Middle East, to inspire heroism in battle. Local landlord Sir Robert Savage prior to any battle ordered his troops to take a good drink of 'aqua vitea'. With the mind-changing effect, it has it is understandable why such practices existed and still exist.

In Ireland we have the following terms to describe the spirit, Aqua Vitea (water of Life), Iskebaghah (water of life), Isquebeoh ( living water), the latter two are Gaelic, here we can see how close the pronunciation of the word 'whisky' is to the Gaelic 'Iske' or 'Isque' meaning water. Wheaten malt was used for the production of 'aqua vitea' and production throughout Ireland expanded dramatically after the dissolution of monasteries by Henry VIII in 1540. The skills which once were contained within monastic walls and the dwellings of the rich and affluent, went out into the wider world where it spread like wildfire, allowing anyone to freely produced it without restriction.

Those in power soon realised the monetary potential of whiskey, Henry VIII tried many ways to curb the illegal production. He introduced a law that would see only one producer in each borough town and if anyone else was caught producing illegally, they would be fined 6s 8d which was a lot of money in 1550. He also placed a restriction on the supply of wheaten malt to ‘any Irishman's' country, which obviously highlights the widespread use of 'aqua vitea' or whisky in Ireland. The king and later the government introduced licensing and duty on both malt and production. In 1661 a duty of 4p was levied on every barrel produced. The duty kept rising through the years with kings and governments always devising new ways to maximise the income from controlled production.

This increased illegal production to a point where it swamped the market, people were not buying legal spirit instead they were buying ‘illegal still’ or indeed produced it themselves, the illicit stills and distilleries in Ireland were virtually out of control at one stage. During the first three years of 1800 revenue men backed by the military found and destroyed 19,000 stills, in 1806 of the 11 million gallons of whisky produced legally in Ireland, 4 million were illegal. Heavy legislation came into force which saw fines and jail for those involved in distillation, any townland where stills or associated artefacts were found, were levied a townland fine which became the responsibility of the people living there to pay. In a seven-year period from 1807-14, the average yearly amount levied was £50,989.

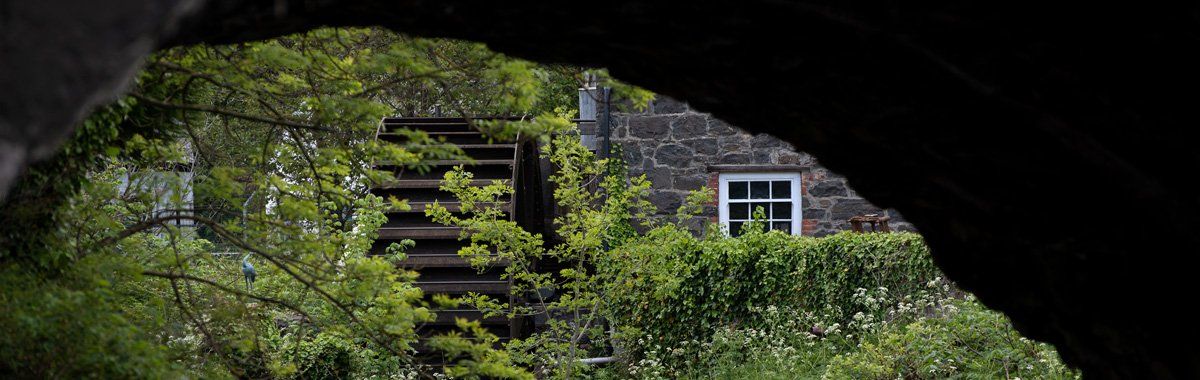

In poor rural areas an illegal still or distillery was seen as an employer, it provided an income for poor families and a money earner for the producer. The market was not drying up but rather increasing, so basically it became an illegal cottage industry which flourished. As the government became more determined to seek and destroy stills, those using stills became even more determined not to get caught. To avoid the townland fines, distilleries were set up on townland borders, they set up in caves, on islands and even on boats floating on a river or lake. Revenue men were frequently kidnapped and held until after the court appearances to prevent them giving evidence. The distiller's went to great length to conceal the stills too.

One story tells of a revenue officer following a young boy with a horse which had a bag of malt on its back, he followed and watched where it stopped, he observed the boy pulling the bag off the horse and it falling to the ground and disappearing. The officer went to get help and returned later in the night to the same spot but found nothing. He then noticed some loosely cut brambles lying on the ground below these he found some loose sods and a trap door leading to a small underground cavern. He followed the cavern to the end, where he discovered a complete distillery at work supplied by an underground stream. The smoke was taken away by piping and joined into the chimney of the distiller’s house some distance away.

Another illegal distillery operated for years disguised beside a lime kiln. The lime kiln was in continuous operation and the smoke from the distillery merged with the lime kiln bringing no suspicion. In 1820 the revenue police were established and by 1833 around 1200 men were employed specifically to target areas where illegal production was known to be highest. The revenue police were effective but they did not stop illegal stills and distilleries. Along with all of this you had government licensing regulations for distilleries. The production size that would qualify for a license changed frequently, along with this duties levied on production and malt went up and up. A duty rise or a change in licensing regulations could mean that a legal distillery would become an illegal distillery virtually overnight.

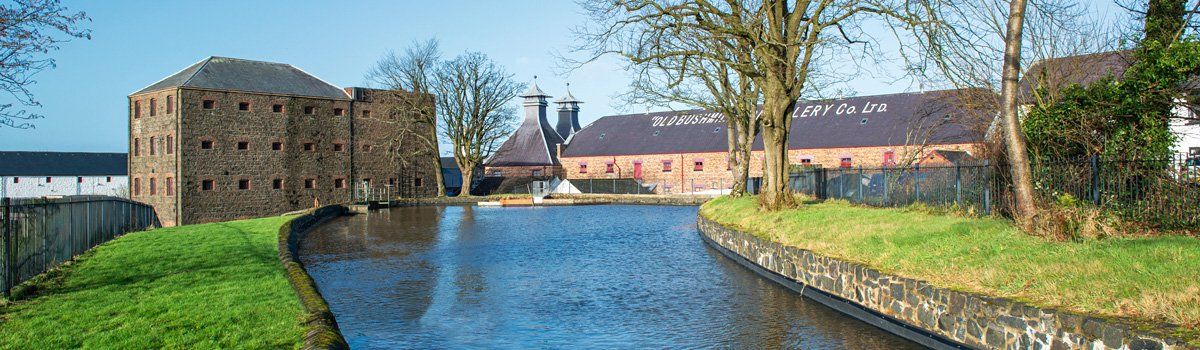

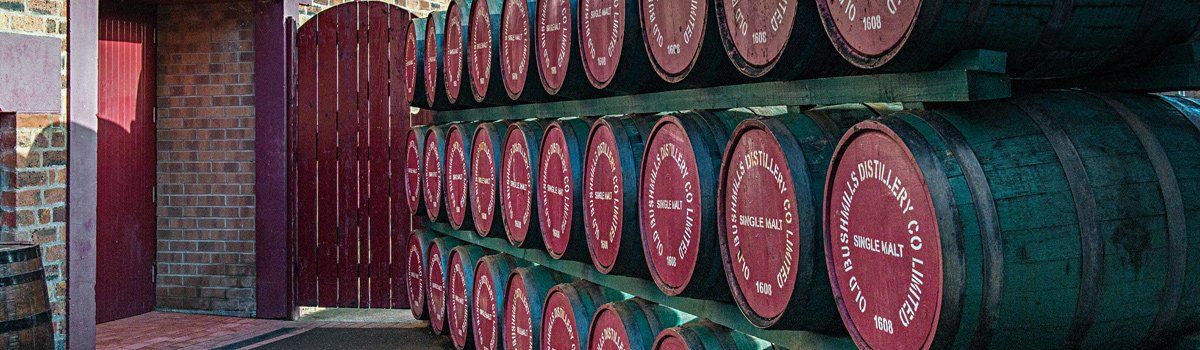

This fact partly answers why we don’t exactly know what happened to the license granted to Thomas Phillips in 1608, that legal distillery most probably went illegal at one or more times in its existence. The reference to the Bushmills distillery being run by smugglers in 1743 suggests that it was illegally operating, Smuggling was common practice between Scotland and Ireland. It may be the reason we have no information about Bushmills Distillery until it was registered. Let’s face it, if you were operating an illegal distillery you would not want too much information to be public or the revenue police would know. Illegal distilling dropped off due to a revision of duty, encouragement and licensing of smaller distilleries and tighter controls. Illegal stilling has never gone away completely, even today you will find the odd illicit still carrying on a traditionally rural practice.

All Rights Reserved | Art Ward

© 2026